When people talk about learning a new language, one word always comes up: grammar. For many learners, it’s the most intimidating part of studying a language. Grammar books are often filled with tables, rules, and exceptions that seem endless. Yet, grammar is much more than a set of complicated rules; it is the invisible structure that makes language work. Without grammar, communication would be chaotic and unclear. But what exactly is grammar? Why do we need it? And how does it shape the way we think and speak?

The Meaning of Grammar

At its most basic level, grammar is the system of rules that governs how words are formed and combined to create meaningful sentences in a language. It defines how we use sounds, words, and sentences to express ideas. Grammar tells us how to make nouns plural, how to arrange words in order, and how to mark time using tenses.

For example, in English, we say “She goes to school” rather than “She go to school.” The difference comes from grammar — specifically, subject-verb agreement. Grammar allows listeners or readers to understand who is doing what, when, and how.

Every language has grammar, even those that have never been written down. Grammar is not something created by teachers or textbooks. It is a natural feature of all human languages, developed by speakers over time. People use grammar intuitively from childhood, long before they can explain it consciously.

The Components of Grammar

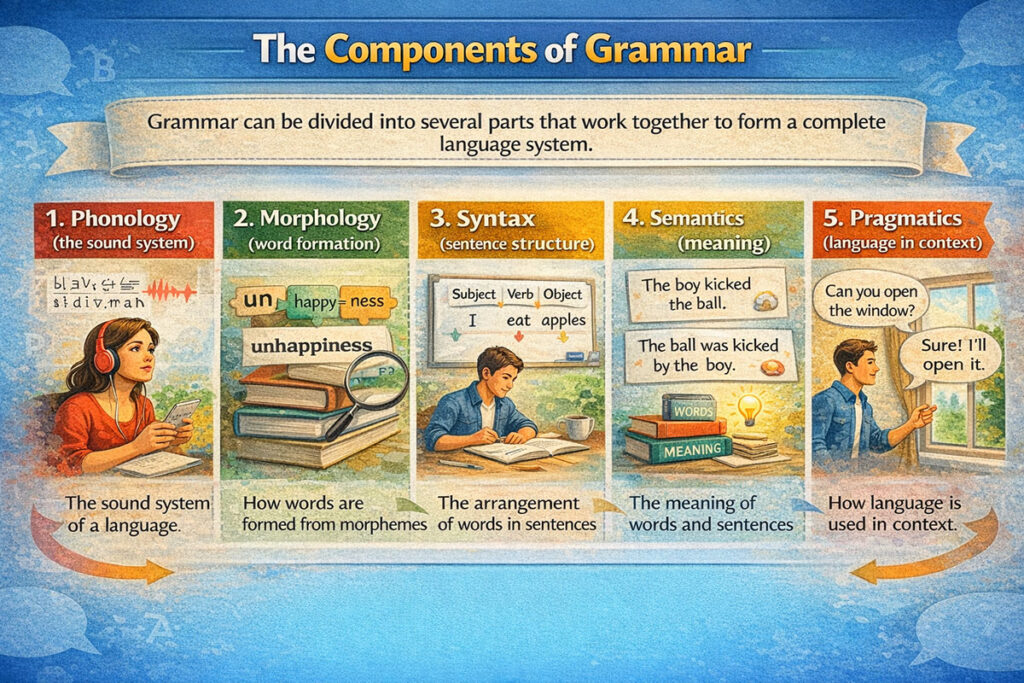

Grammar can be divided into several parts that work together to form a complete language system.

1. Phonology (the sound system)

Phonology deals with the sounds of language and how they are organized. It includes the rules that determine how sounds can combine and how intonation affects meaning. For example, the difference between “record” (noun) and “record” (verb) in English depends on stress patterns.

2. Morphology (word formation)

Morphology studies how words are built from smaller units called morphemes. A morpheme is the smallest unit of meaning in a language. For example, the word “unhappiness” contains three morphemes: un- (a prefix meaning “not”), happy (the root), and -ness (a suffix meaning “state or quality”).

Morphology explains how new words are created, how verbs change form (like walk, walked, walking), and how plural or possessive endings are added.

3. Syntax (sentence structure)

Syntax refers to how words are arranged into sentences. Each language has its own word order patterns. English generally follows the Subject–Verb–Object structure: “I eat apples.” In Japanese, the structure is often Subject–Object–Verb: “I apples eat.”

Syntax helps us understand relationships between words and how meaning changes when word order changes.

4. Semantics (meaning)

Semantics is the study of meaning in language. It focuses on how words, phrases, and sentences convey information. For example, “The boy kicked the ball” and “The ball was kicked by the boy” mean the same thing semantically, even though they differ syntactically.

5. Pragmatics (language in context)

Pragmatics deals with how people use language in real situations. It includes tone, politeness, and social norms. For instance, “Can you open the window?” is grammatically a question, but in context, it functions as a polite request.

Together, these components create a system that allows us to express complex ideas with clarity and precision.

Grammar as a System

Grammar is often compared to the rules of a game. Just as players must know how a game works to play it correctly, speakers must understand grammar to use language effectively. However, grammar is not a fixed set of rules created by authorities; it evolves naturally over time.

When we say “grammar,” we can refer to two things:

- Descriptive grammar – how people actually use language.

- Prescriptive grammar – how people should use language according to traditional norms.

Descriptive grammar looks at real-life speech. Linguists who study descriptive grammar observe patterns and try to explain them. For example, many native English speakers say “Who are you talking to?” instead of “To whom are you talking?” A descriptive grammarian would say both are correct within different contexts.

Prescriptive grammar, on the other hand, sets formal standards often used in education or writing. It tells us which forms are considered “proper.” For instance, prescriptive grammar insists that sentences should not end with prepositions, even though many native speakers do this naturally.

Both perspectives are useful. Descriptive grammar helps linguists understand how languages function, while prescriptive grammar provides consistency in writing and formal communication.

Why Grammar Matters

Some people think grammar is unnecessary or overly rigid, especially in casual conversation. But grammar is what gives language structure and meaning. Without it, we would struggle to convey even simple ideas accurately.

Consider the difference between:

- “The dog bit the man.”

- “The man bit the dog.”

The same words appear in both sentences, but grammar changes their order and therefore their meaning. Grammar determines who performs the action and who receives it.

Grammar also helps us distinguish between different time frames, levels of certainty, and attitudes. When we say “She might go” versus “She will go,” grammar marks the difference between possibility and certainty.

In written communication, grammar ensures clarity and professionalism. Readers may judge credibility or intelligence based on how correctly and clearly someone writes. In spoken language, correct grammar helps avoid misunderstandings and supports effective communication.

How Grammar Develops in Children

Children acquire grammar naturally as part of language development. They start by learning words, then begin combining them according to patterns they hear around them. At first, children may say things like “Me want cookie” or “She goed home.” Although incorrect, these sentences show that the child understands basic grammatical rules such as subject–verb–object order and past tense formation.

According to Noam Chomsky’s Innatist Theory, children are born with an innate ability to understand grammatical structures. Their brains contain a “Language Acquisition Device” that allows them to identify the patterns of their native language quickly.

Other theories, such as Behaviorist and Interactionist approaches, emphasize imitation and communication with caregivers. Whatever the mechanism, all children eventually master the grammar of their language by interacting with others and experimenting with speech.

Grammar Change and Language Evolution

Languages are constantly evolving, and grammar changes with them. Old forms disappear, and new ones emerge. For example, in Old English, double negatives were grammatically correct (“I don’t know nothing”), but modern English now views them as incorrect.

Likewise, verb forms, word order, and sentence structure shift over time. The phrase “Thou art” eventually became “You are.” Even new slang and informal expressions follow grammatical patterns, showing that grammar adapts to changing usage.

Some grammar changes happen through contact with other languages. When speakers of different tongues interact, they often borrow words, structures, and expressions. English, for example, absorbed grammatical influences from French, Latin, and Norse.

Today, technology and global communication continue to shape grammar. Texting and online communication have introduced new conventions, such as abbreviations and emoji, which function like modern punctuation and tone markers.

Grammar in Different Languages

While all languages have grammar, they vary widely in how they express meaning. For instance:

- English relies heavily on word order. The difference between “The cat chased the dog” and “The dog chased the cat” lies in position, not word endings.

- Latin and Russian use inflections, changing word endings to indicate grammatical relationships.

- Chinese uses word order and context but has little inflection, meaning the same word form can serve multiple functions depending on placement.

These differences show that grammar is not universal in form, but it is universal in function. Every language needs a system to organize meaning.

Grammar and Thinking

Many linguists and psychologists believe that grammar influences how we think. This idea, known as linguistic relativity, suggests that the grammatical structures of a language shape how its speakers perceive the world.

For example, some languages mark gender in every noun, such as Spanish (el sol for “the sun,” masculine, and la luna for “the moon,” feminine). Research shows that speakers of such languages may describe these objects differently compared to speakers of languages without grammatical gender.

Similarly, languages that use specific verb forms for tense, such as English, may encourage speakers to focus on time, while others, like Chinese, focus more on context. Although the relationship between grammar and thought is still debated, it is clear that language structure affects how we organize experience.

Grammar in Language Learning

For language learners, grammar is both a challenge and a key to fluency. Understanding grammar helps learners create sentences correctly and recognize patterns quickly.

However, memorizing rules alone is not enough. Effective grammar learning combines theory and practice. Learners benefit most from contextual learning, where grammar is taught through real examples, conversations, and writing.

Modern teaching methods focus on communicative grammar, encouraging learners to use grammar naturally rather than recite rules. Instead of saying “this is the present perfect tense,” teachers might provide examples like “I have seen that movie” and explain when and why it is used.

Technology also plays a growing role. Language-learning apps now use interactive exercises, speech recognition, and artificial intelligence to help users master grammar intuitively.

The Role of Grammar in Communication

Grammar is not about perfection or memorizing strict rules. It is about making meaning clear. Different situations call for different levels of grammatical formality. Speaking with friends, writing an academic paper, and sending a business email all require different tones and levels of correctness.

Native speakers often break grammatical rules in casual conversation, using contractions, fragments, or slang. What matters most is understanding and being understood. Good grammar supports this goal by providing a shared structure for expression.

Ultimately, grammar is not the enemy of creativity; it enables it. Writers, poets, and speakers use grammar to shape rhythm, tone, and style. Even breaking grammatical rules can be powerful when done deliberately for artistic effect.

References

- Crystal, D. (2003). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. Cambridge University Press.

- Fromkin, V., Rodman, R., & Hyams, N. (2018). An Introduction to Language. Cengage Learning.

- Pinker, S. (1994). The Language Instinct. William Morrow.

- Radford, A. (2009). Analysing English Sentences: A Minimalist Approach. Cambridge University Press.

- Yule, G. (2020). The Study of Language. Cambridge University Press.